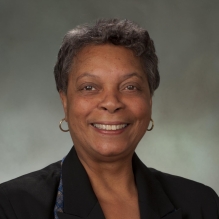

Bill Engelbrecht

William (Bill) Engelbrecht’s fondest memories of teaching at Buffalo State occurred knee-deep in soil. It was there that the professor emeritus of anthropology immersed himself in evidence of the past, documenting findings, and connecting with undergraduates during the college’s Summer Archaeological Field School.

"This type of work is more like learning a foreign language. You are acquiring a new skill. You have to keep careful records and analyze the data,” said Engelbrecht, a trustee with the New York State Archaeological Association who taught anthropology from 1973 to 2003 and received the Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching in 1990.

For six weeks each summer, students in the field school search Beaver Island State Park for artifacts, gleaning information on indigenous people of Western New York going back thousands of years. At Old Fort Niagara, students look for remnants of the War of 1812 and for evidence of trade between the French, British, and Native Americans. In the process, students learn how to excavate stratigraphically and document data, which are crucial skills for archaeological careers, said Lisa Marie Anselmi, chair and associate professor of anthropology.

It’s also a transformative experience, noted Sue Maguire, assistant professor of anthropology, who now oversees the Old Fort Niagara fieldwork.

“I’ve had students tell me the field school was the best experience of their lives,” she said.

Engelbrecht wants to ensure that students continue to have this transformative experience. In 2009, he established the Summer Fieldwork Anthropology Scholarship Fund, which provides at least one student scholarship per summer. Recently, he set up a charitable gift annuity (CGA) that will endow the fund into perpetuity.

“For some students, this scholarship means the difference between participating and not participating in the field school,” said Anselmi.

Engelbrecht understands the need.

“I know it’s hard when you are a student to make ends meet,” he said. “When I was teaching, I saw it over and over again—students really struggling, sometimes working 40 hours a week while carrying a full caseload of classes.”

Engelbrecht is soft-spoken, a self-described introvert who exhibits a kind, easy-to-know manner. Even non-majors who only took his introductory Human Origins course remember him. He occasionally runs into former students around town and to them he is still “Dr. E.”

“He was well-loved. Although he officially retired, he is still a regular fixture on campus,” said Anselmi. “He is here at least twice a week continuing his research.”

Fieldwork is not only dear to Engelbrecht’s heart; it’s also the best way for students to learn, in his opinion.

“The American education system doesn’t do a good job of teaching science,” he said. “Students respond much better to hands-on situational learning.”

That type of learning clearly pays off. A number of his students have gone on to pursue doctorates in anthropology. Some now work in higher education. Others found positions in cultural resource management or with non-profit organizations such as Habitat for Humanity.

Now, thanks to Engelbrecht’s generous endowment, his love of teaching and discovery will live on for generations to come—with each turn of the soil, each new find.